Remembering Des: Trying to comprehend the incomprehensible

It has been said that we know more about the intricacies of our vast planet than we do about the human mind.

Tiny as it may be compared to the size of our world, it is very complex in composition. We may know it physically, superficially, but its inner workings remain largely a mystery.

Misunderstood

While great advancements have been made in recent decades in dealing with deadly physical diseases, treating psychological problems still relies on, to a large extent, a trial-and-error approach. Generalisations on behaviour can be made and on many occasions are accurate, but the very essence of one’s uniqueness emanates from his or her own brain.

We never truly know what another person is thinking, how he or she is feeling. It is, perhaps, medical science’s greatest challenge: to find an effective, lasting way to treat those suffering from mental illness.

I used to have quite an unsympathetic view of people who were going through depression. My thinking was, ‘stop feeling sorry for yourself. Snap out of it.’

Time and closer dealings with depressed individuals have seen me change this stance. When one is in such a state of mind, nothing is seen in a positive light. Both the inward and outward filters are at best a dark shade of grey, at worst a bleak, hopeless black.

Nothing that one says or does seems capable of altering this. What’s more, the feelings are generally irrational. One can highlight to the sufferer all the reasons why he or she should feel grateful for life but it’s usually a pointless exercise. Yes, the darkness can pass, but it’s normally just a brief respite.

‘While I still see suicide as a horrible act, I’ve come to understand a little better the complete hopelessness that one feels in order to take that final, dreadful step.’

At most we know it’s a chemical imbalance in the mind and with the right mix of medication, some people can learn to cope. Finding that balance is the tricky part, however.

For those who don’t get that help, the ultimate solution becomes the only option to escape the constant doom.

Similar to how I used to think about depression, I used to also view very negatively that irreversible «cure» chosen by some sufferers. I saw suicide as an utterly selfish act. The depressed ends his or her suffering but leaves behind loved ones who have to try to come to terms with the fateful decision.

Again, though, my perception has changed with experience. While I still see suicide as a horrible act, I’ve come to understand a little better the complete hopelessness that one feels in order to take that final, dreadful step.

Demons return

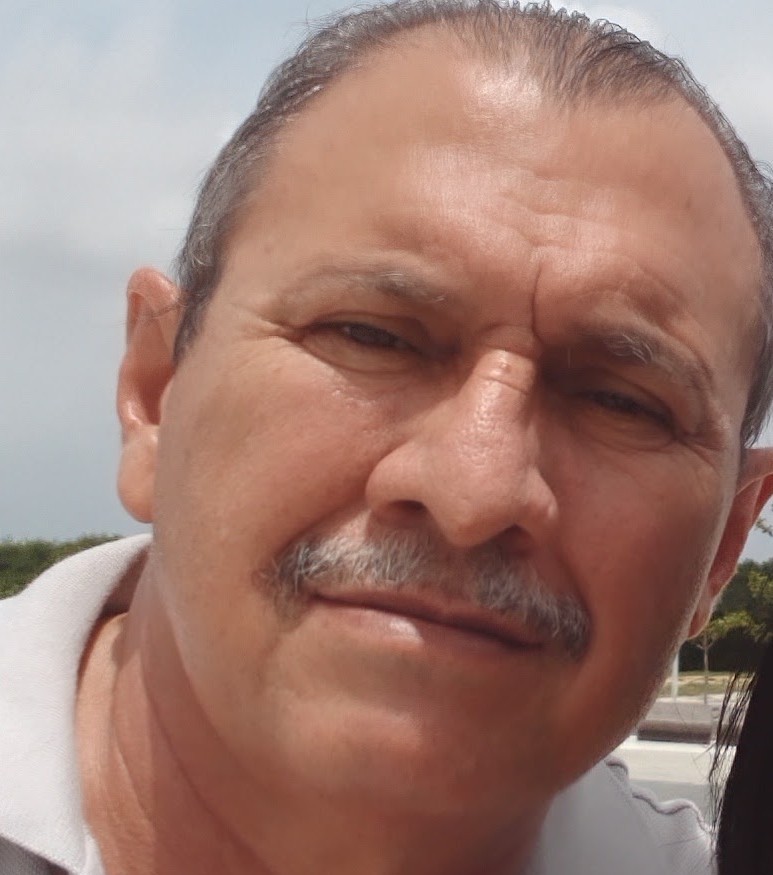

Just over a year ago, I interviewed Des McAleenan, the Irish goalkeeping coach who landed what he described as a dream job with Colombia’s men’s football team. In that interview, he spoke candidly about the ‘demons’ that had taken over his mind in the past.

He was, however, in a much happier place in January 2020. There was much to look forward to — World Cup qualifiers against some of the best nations on the planet, a Copa América in front of a home Colombian crowd. Des’s present and future looked bright.

Then, along came covid. The World Cup qualifiers and Copa América were postponed. With his job paused, Des left Colombia and returned to Ireland.

Initially, however, everything was fine. He even found, so he told me, more fulfilment in life by training some children in his native Dublin in the Irish summer. Facebook posts showed him enjoying daily runs along the north Dublin coast.

It was what seemed from afar a fairly innocuous ankle injury that plunged him into darkness again. He began to worry about his career. In his early 50s, if he couldn’t carry out training properly, would he be let go?

In any case, he was involved with the Colombian set-up for the World Cup qualifiers in October. A straightforward home win over Venezuela and a very credible draw away to Chile did nothing to improve his state of mind.

He was ruled out for the November round of qualifiers after he contracted covid. As Colombia slumped to heavy defeats at home to Uruguay and away to Ecuador, Des was in quarantine in Bogotá’s five-star Grand Hyatt Hotel.

We had a telephone call at the time and he told me how it just didn’t make sense that he felt so depressed. Financially he was fine and while manager Carlos Queiroz’s position was on the line after the damaging losses, Des was rather sanguine about the prospect of losing his job.

‘The darkness just got darker. The demons wouldn’t go away. To get rid of them, he had to get rid of himself.’

He joked, true as it was, that he hadn’t actually lost a game with Colombia. Also, listening to my visa travails, lack of a steady job and general uncertainty, he said I should be the one depressed, not him. Of course, it doesn’t work that way.

Queiroz’s tenure — and by extension Des’s — was indeed ended shortly afterwards. ‘A shit time all round’ was how Des put it to me in a WhatsApp message.

Nonetheless, he told me there was a potential coaching job with a club in the US, in Salt Lake City. That prospect made him feel a lot better, so he told me. The ankle, which seemed like a physical manifestation of the mental problems he was battling, was still annoying him, however.

He went back to Ireland again in December.

The last message I received from him was on 30 December. It read: ‘Back in Dublin Brendan, it’s a fuckin’ nightmare. Having a very difficult time coming to terms w[ith] the problem w[ith] my ankle. How are you? Still in Colombia?’

Less than two months later Des took his own life.

I only knew him for just over a year but during that time we had some long and deep conversations. Different as we were, I felt a connection with him.

I don’t know what to make of his decision to kill himself. It doesn’t make sense.

I tried to offer words of encouragement, tried to make him see the positive side of things. But the darkness just got darker. The demons wouldn’t go away. To get rid of them, he had to get rid of himself.

Adiós, Des. Adiós.

*****

For those in Colombia troubled by what’s written in this article, Bogotá has the phone line 106, ‘El poder de ser escuchado’, which offers support in times of crisis including cases of sexual violence, suicide and substance abuse. The 24-hour service is also available via WhatsApp on 300 7548933.

The city also operates the Línea Psicoactiva on 01800 0112439 (Mon-Sun from 7.30 am-10.30 pm) Facebook and Skype at Psicoactiva and WhatsApp on 301 2761197.

In Ireland, you can contact the following:

Samaritans 116 123 or email jo@samaritans.org;

Aware 1890 303 302 (depression, anxiety);

Pieta House 01 601 0000 or email mary@pieta.ie (suicide, self-harm).

_______________________________________________________________

Listen to Wrong Way’s Colombia Cast podcast here.

Facebook: Wrong Way Corrigan — The Blog & IQuiz «The Bogotá Pub Quiz».

Comentarios