Ingresa o regístrate acá para seguir este blog.

Examples of how not to pursue self interest and do the right thing when helping a disadvantaged group. Afro-Colombian leaders ask for change in execution of a specific heading of Plan Colombia.

Part II

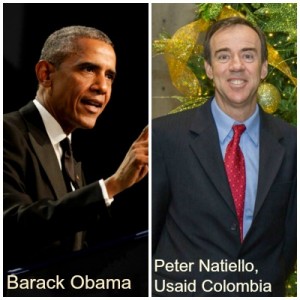

It seems clear that Obama’s shift in relation to other nations’ civil societies is sided with the strategic interest of the population which is being supported over the interest of USA’s public diplomacy, as it has been practiced. It is also clear that a shift in philosophy is not something that can be implemented overnight.

It seems clear that Obama’s shift in relation to other nations’ civil societies is sided with the strategic interest of the population which is being supported over the interest of USA’s public diplomacy, as it has been practiced. It is also clear that a shift in philosophy is not something that can be implemented overnight.

The interesting thing about the Afro-Colombian case is that the new direction of the American aid was requested beforehand and with specific ways to achieve it. Two observations arise, regarding the USAID’s Program for Afro-descendants and Indigenous People, which is in the last stages of utilizing the 62 million budget from Plan Colombia:

1) It hasn’t empowered Afro-Colombian leadership as a change agent, which was a promise; and,

2) It has not influenced strategic variables for the development and well-being of the black population.

Two of the practices that don’t empower and that the shift in philosophy would render obsolete are the “take it or leave it” approach and the brand promotion. Since the leaders of the disadvantaged group are treated as fund recipients and not as communicators in a representative board, the donor decides without considering explanations for each case. The donor’s attitude is one of “We will offer this amount of funding for your proposal; take it or leave it.” This has driven three disaffected organizations to say “We have decided not to pursue more USAID donations under the current conditions.”

The imposed branding rules are very rigid. The donor specifies where to put its logos in the dominant visual fields, which in some cases can be counterproductive, given our society. The public interpretation is often “So this is a Gringo idea, not yours, and you are the ones getting paid,” when the reality couldn’t be more different.

In general, when there is an organization empowered for a cause, the donor takes excessive credit for the support given. And when there is no empowerment in civil society, it acts on its own as another agent substituting Afro-Colombian leadership… making mistakes that would be unforgivable in the United States. Discretion is banished; in its place, a dynamic is created that does not regard the interests of the supported group.

No Afro organization would invite a bank today as an ally for an award for Inclusive Media. It would give the wrong impression that it has made an advance in the difficult conversation with the financial industry and their choice not to hire black people, specifically in the areas of retail and customer service. Nevertheless, the program for Afro-descendants and Indigenous people did just this, while failing to offer any kind of explanation.

When a communications agency asks for support with the visit of a popular Afro-Colombian figure, like a fashion designer, the answer is yes; but when it involves helping a symbolic institution which is experiencing a public opinion crisis, like the basketball team “Cimarrones” from Chocó, then the answer is no. These are examples that prove Obama right, and show that he should be listened to more in Bogotá. What to do? To be continued…

This text was originally published in Spanish (05/12/2015) in one of Colombia’s national papers.

Translation by Alejandro Maldonado.