Ingresa o regístrate acá para seguir este blog.

The 15 years of Plan Colombia call for a balance of their impact for the black population. Afro-Colombian leaders ask for change in execution of a specific heading of Plan Colombia.

Part III:

Fifteen years ago, local and social control regarding the United States Partnership would have seemed exotic. “It’s the donors’ money, what’s important is they spend it here.”

Yet, still the predominant attitude in organizations is to “be on good terms” with the United States Embassy, and the objective, “to be taken into account” for future donations.

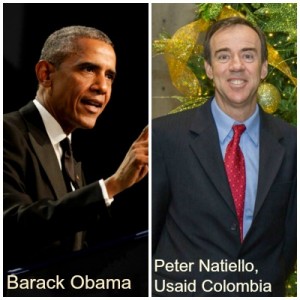

In what moment did the matter started to be seen differently? Obama just noticed the new trend, he did not start it with his speech in the Civil Society forum.

In what moment did the matter started to be seen differently? Obama just noticed the new trend, he did not start it with his speech in the Civil Society forum.

“Empowering for change” is now a recurring theme, even if prior practices still remain. But it is already known that actions speak louder than words, and actions have thus far been lacking.

What Obama did was accept, tacitly, of course, that there is an unsustainable moral and ethical situation regarding the US government, specifically in its relations with other countries’ civil societies.

Obama accepted that they possibly have been “defending self interest” instead of “doing the right thing” when helping a disadvantaged group. By doing so, he maintains his government at the forefront of the conversation, preserving the best possible position for when the necessary change happens.

An opportunity to begin such change in relation to the Afro-Colombian population is what has resulted from the 15 years of the Plan Colombia.

To what objectives and standards will the impact of the invested resources in the population be upheld? To some embassy or Colombian government standards, or to some joint objectives agreed upon by the beneficiary population?

One crucial observation to be made of the Program for Afro-descendants and Indigenous people from USAID is that, 62 million dollars later, the results do not reflect the strategic objectives of the Afro population, but rather the program’s own objectives, established for and by itself.

A forum to study this balance would have to include the question of whether the Afro dependency of the Plan Colombia has contributed more to the status quo than to the change in the position of the black population in this country.

As Obama said, civil society is indispensable for change. Here, not only has the civil society not been empowered or strengthened (to speak of national powers), but a fixed-term program has been created (2016), and instead of supporting the construction of possibilities for the population, it has set aside institutions that will outlast it.

To the dynamic of traditional public diplomacy, preoccupied with the visibility its donations, was added the corporate interest of Acdi Voca, to the point that by acting as two of the creditors, a part of the public believes them to be two of the donors.

Avoiding repetition with the unused resources from Plan Colombia is the starting point for a conversation between Washington and Bogotá.

Ambassador Whitaker and the director of USAID Colombia, Natiello, can decide if the legacy for their missions in Colombia will consist of making a profound change in the sense indicated by Obama or not.

The first assembly of 2016-2019 mayors from municipalities with large Afro populations, in early 2016, will be a good starting point. The end (for now).

This text was originally published in Spanish (12/12/2015) in one of Colombia’s national papers.

Translation by Alejandro Maldonado.